In order to build a nation of today through the eyes of tomorrow we must first engage what was yesterday. Yesterday in terms of where we came from, who we are and how to use these findings as a mechanism to empower and change where, as a nation, we are heading.

Where The Landscape is the Only Surviving Witness.

Most Caribbean authors have been preoccupied by particular themes and have adhered to mutual pathways, while often contrasted in method/style and writing. The probability or unlikelihood of the account of one’s story, when the actual thought of the individual has been crushed by slavery and colonialism; the circumstances of advent of a new Caribbean identity; the analysis of the past, writing in exile and lastly, landscape and nature: where the environment or surrounding tells the story is an essential foundation of the examination of oneself and their community. Caribbean literature takes on a scrupulous urgency and prominence because of the major role it plays in its attempt to recreate a divergent cultural identity that evades the incarceration of colonial past. Where the landscape is the mirror the assimilation of colonisation and a fractured history is analytically examined demonstrating its importance and correlations. According to ‘An Introduction to Post-Colonial Theory’, it expresses what the Caribbean poet Lorna Goodinson says:

Most Caribbean authors have been preoccupied by particular themes and have adhered to mutual pathways, while often contrasted in method/style and writing. The probability or unlikelihood of the account of one’s story, when the actual thought of the individual has been crushed by slavery and colonialism; the circumstances of advent of a new Caribbean identity; the analysis of the past, writing in exile and lastly, landscape and nature: where the environment or surrounding tells the story is an essential foundation of the examination of oneself and their community. Caribbean literature takes on a scrupulous urgency and prominence because of the major role it plays in its attempt to recreate a divergent cultural identity that evades the incarceration of colonial past. Where the landscape is the mirror the assimilation of colonisation and a fractured history is analytically examined demonstrating its importance and correlations. According to ‘An Introduction to Post-Colonial Theory’, it expresses what the Caribbean poet Lorna Goodinson says:

“When is post-coloniality going to end? How does the post-colonial continue?”

A pertinent question and one in which compounds the problems of periodizing. In this sense, to also ask the question “Who is post-colonial?’ seems to assume identities already in place, which can then be judged to be post-colonial or not. Whereas, for many groups or individuals, post-colonialism is much more to do with the painful experience of confronting the desire to recover ‘lost’ pre-colonial identities, the impossibility of actually doing so and the task of constructing some new identity on the basis of that impossibility. ‘Who is post-colonial?’ then becomes at least temporarily or partially unanswerable: to the extent that major reformulations are taking place with the identities of the formerly colonised and diasporic groups, attempts to define or circumscribe in advance the content of that ‘Who?’ are premature. It even goes on to explain a rather different and more disturbing, form of amnesia identified by Dirlik:

‘Post-colonial, in other words, is applicable not to all of the postcolonial period, but only to that period after colonialism when, among other things, a forgetting of its effects has begun to set in. In this perspective, post-colonialism appears almost a pathology, a diseased sign of the times.’ (Childs 7,14,17).

The Struggle of History and Identity in Literature

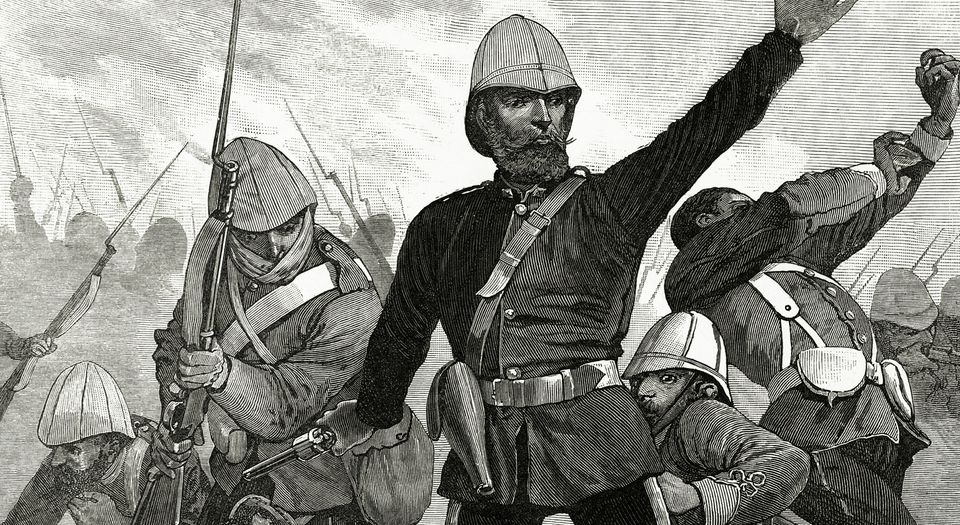

The overall experience of slavery (mentally, physically and emotionally), colonialism, exile, emancipation and independence has sculpted many West Indian environments, somewhat constituting to a mutual unity of familiarity that can be set apart particularly as West Indian. West Indian literature is therefore an outcome or product of this experience. Its outset in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and its development in the twentieth century echoes the advancement of West Indian battle with history, with social and political adjustments and with an enigma in identity definition. Laurence A. Breiner in ‘West Indian Poetry and its Audience’ mentions Braithwaite’s keynote address where he questions the topic,“how does the writer develop a new sense of community for a multi-directional culture with a history of slavery, colonialism and uncertain independence?”(1). He argued that “the integrating principle must be sought in the submerged continuity of the ‘Little Tradition’ the culture of ordinary people” (1). He repeated that “each race and group in the West Indies needs to descend into its own past before a truly multi-racial society, a Creole society can be anything more than a glib ideal” (1).

The Sankofa bird is a mythical bird from an African proverb that flies forward with its head turned backwards. It is an African symbol which means one looks back but moves forward while engaging the past. Sankofa is an Akan term which literally means, “to go back and get it.” Broken up into syllables ‘San’ means ‘to return’, ‘Ko’ means to ‘to go’, ‘Fa’ means ‘to look, to seek and take’. There is also an egg in the mouth of the bird which signifies ‘gems’ or knowledge of the past upon which wisdom is based; it also represents the generation to come that would benefit from that wisdom. The Akan believe that the past illuminates the present and the search for knowledge is a lifelong process (Sweet Chariot: the story of Spirituals).

Which brings up the argument of how much or how long should one keep looking backward and how much should one engage their past? If one engages their past where they are constantly hurt by it, then that can become problematic and this is where Walcott says that,

“you should not engage the past to be hurt but it’s really to engage the past to be free”.

Which again one should question and ask themselves to what extent as Creoles’ does one engage history and how are the materials handled after being engaged? Understanding that yes, Creoles’ have been hurt, there is still the urgency and mandate to move forward; identity as a nation still has to be built.

Nicolás Guillén’s 1947 poem, “Elegia”, begins with an insight explaining, “One must remember” or “we must remember” or “it must be remembered” to memorialize a history that has no surviving witnesses except nature itself (DeLoughrey, Gosson, Handley 1). It simply states being ignorant of the past is unacceptable even though it cannot be known. Even when language escapes one in explaining the absolute identity of the Caribbean and the writer, it should not stop one from still attempting to do so. Edouard Glissant comes to the conclusion that the Caribbean nature and culture has not been brought into a formative relation. He however says the Caribbean

“landscape itself is its own monument: its meaning can only be traced on the underside. It is all history” (DeLoughrey, Gosson, Handley 2).

Both Wilson Harris and Guillén Glissant imply the landscape is inundated by “traumas of conquest” that the land itself has become a mute history or record of a “fight without witness” so that a gesture as an act to destroy the land is an act of violence to the collective memory (DeLoughrey, Gosson, Handley 2).